Aldo Leopold, vanished “soundscape,” and wind turbines

Sep 21, 2012

.

.

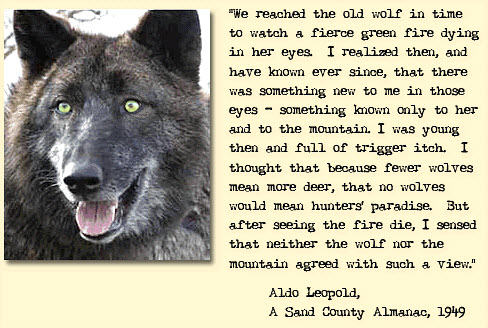

Editor’s note: In a short list of environmental philosophers, Aldo Leopold’s name would rank near the top. I refer to true environmental philosophy, not the Green hysteria machine of corporate wind energy. It was Leopold who coined the phrase, “land ethic,” and Leopold who exhorted us to “think like a mountain!”

I see no evidence of either land ethic or thinking like a mountain when I scan the ridgelines of Maine and Vermont, where gigantic machines entombed in cement beat the thin, delicate air once inhaled by living, breathing forests.

The entire ancient earth thinks prodigiously,

and the murmur of its great trees grows”—Rainer Maria Rilke

It was Leopold who spoke reverently of watching the green fire go out of the eyes of a wolf he shot in his callous youth—vowing never to do so again. If you have never read his Sand County Almanac—you must. It’s a life changer.

He died in 1948, the year I was born, overcome by smoke while fighting a brush fire near his beloved Wisconsin wilderness camp.

The article, below, was sent to me by Boyce Sherwin, a friend and neighbor in my neck of the woods. The article says nothing about wind turbines—not explicitly, that is. Implicitly, it says volumes. For those of you living in rural Ontario, rural France or Italy or England or Australia, rural Maine, or wherever turbines and their headache-pounding infrasound and banshee roar have commandeered your soundscape, you will grieve for the lost symphony of quietness, where “peace comes dropping slow.”

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honeybee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a-glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear the water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements gray,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core—Wm. Butler Yeats, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (1892)

.

“Aldo Leopold’s Field Notes Score a Lost ‘Soundscape'”

—Terry Devitt, reprinted in ScienceDaily (9/18/12)

Among his many qualities, the pioneering wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold was a meticulous taker of field notes. Rising before daylight and perched on a bench at his Sauk County shack in Depression-era Wisconsin, Leopold routinely took notes on the dawn chorus of birds. Beginning with the first pre-dawn calls of the indigo bunting or robin, Leopold would jot down in tidy script the bird songs he heard, when he heard them, and details such as the light level when they first sang. He also mapped the territories of the birds near his shack, so he knew where the songs originated.

Lacking a tape recorder, the detailed written record was the best the iconic naturalist could do.

“Leopold took amazing field notes,” says Stan Temple, a University of Wisconsin-Madison emeritus professor of wildlife ecology and now a senior fellow of the Aldo Leopold Foundation. “He recorded his observations of nature in great detail.”

Using those notes, Temple and Christopher Bocast, a University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute graduate student and acoustic ecologist, have recreated a “soundscape” from Leopold’s 70 year-old notes. But the dawn chorus that Leopold heard in1940 no longer exists at the shack, Temple explains. The mix of species today is different due to changes in the landscape and changes in the bird community around the shack.

More noticeable is the thrum of the nearby interstate highway, audible at every hour from Leopold’s storied sanctuary, and the other constant and varied noises of the human animal. Since Leopold’s time, for example, the internal combustion engine has roared to soundscape dominance, whether as an airplane overhead, a rumbling motorcycle, a whining chain saw or an outboard churning on the nearby Wisconsin River.

“The difference between 1940 and 2012 is overwhelmingly the anthrophony — human-generated noise,” explains Temple. “That’s the big change. In Leopold’s day there was much less of that.”

The resurrected soundscape of 1940s Sauk County is the first to be recreated from actual data rather than someone’s imagination of what the past sounded like, says Temple. The work fits into an emerging field of science known as soundscape ecology, which seeks to explain the role of sound within a landscape and how it influences the animals — birds, insects, amphibians, even fish — that live there.

Recently, a rarefied group of scholars who work in the new field met at the Leopold Center, just a few hundred yards from Leopold’s humble shack. The National Science Foundation-sponsored workshop drew not only scientists but philosophers, musicians and others with an interest in natural sounds. Temple gave the opening keynote, which featured the reconstructed dawn chorus.

“Aldo Leopold recognized that you can get a pretty good sense of land health by listening to the soundscape,” Temple says. “If sounds are missing and things are there that shouldn’t be, it often indicates underlying ecological problems.”

The soundscape produced by Temple and Bocast is a compressed version of the chorus described by Leopold, taking 30 minutes of notes and compressing them into five minutes of recording. Bird songs and calls were obtained from the extensive collection housed at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library.

The background sound on which they superimposed the bird songs is all Wisconsin, but Temple and Bocast struggled to find a place where human noise was as it would have been in Leopold’s time: “There are combustion engines on the edge of hearing all the time,” says Bocast, whose dissertation work includes a bioacoustic study low frequency sounds made by spawning sturgeon.

Citing a recent study, Temple points out that in the lower 48 states, there is no place more than 35 kilometers from the nearest road, making it nearly impossible to tune out the hum of human activity, even in places designated as wilderness. “It is increasingly difficult to study natural soundscapes that represent normality,” says Temple, noting that its not just mechanical human noise that’s encroaching. The rain forests of Hawaii, for example, no longer sound like the rain forests of Hawaii. “They sound more like the rain forests of Puerto Rico because the calls of an introduced, invasive tree frog are becoming pervasive.”

Preserving the natural sounds of a place, avers Temple, may be just as challenging as conserving the mosaic of plants and animals that help keep an ecosystem intact. Like smell and sight, “sound can be what you associate with a particular landscape,” something Leopold appreciated and wrote about in several of his well known essays.

By noting and studying the role of sound in the natural world, Leopold proved again to be ahead of his time. Science is only now coming to grips with the totality of the sounds of nature (much like the sound of an entire orchestra) rather than the individual components of the soundscape, according to Temple.

Understanding how nature’s “music” is changing and how much attention we need to pay to the sounds introduced by people, he says, are challenges for soundscape ecologists. And we have much to learn about what the noise people make does to the environment.

Comment by preston mcclanahan on 09/21/2012 at 10:40 am

In New Orleans, around 1900, a form of music was invented that was and is a prime example of democracy. An ensemble consists of six to seven musicians. Each plays a different sounding instrument, but all play the same song together in collective improvisation. According to Alan Lomax, when European composers heard it they were heavily influenced and changed course.

New Orleans in the early decades must have been fairly quiet. Music echoed off Lake Pontchartrain and it bounced around the nieghborhoods.

That reasonably quiet soundscape could have been a part of this musical breakthrough.

Comment by Anonymous on 09/21/2012 at 10:04 pm

I just came in from sitting in my red rocking chair, outside on my stone porch. I like to sit there every night in the dark. I heard this year’s family of coyotes, calling to the moon. I saw the bright moon behind the 150-year-old apple tree. My horse “Hobo” whinnied and snorted—he knew I was there.

It is a bit chilly, so I quietly walked over and piled some straw on top of Bulldozer, my little black pig. He gave a sleepy thank you and yawned. Then I needed a velvet kiss from Hobo. So, even though my knee is sore, I padded through the grass to his fence—of his big valley. The moon lit up the white pattern on his chestnut face. He leaned over and nuzzled me. “God, he smells so good and he feels so warm.” I got my velvet kisses; he got my voice, low in the darkness, almost a whisper calling him my favorite mighty steed.

Sometimes, when I say goodnight to all my furry friends, I say “night night baby duck!” And when asked why I would call a pig or horse, dog or cat by the name “baby duck,” I explain that they are all so pure and innocent. To me they are like a baby duck.

Damn the wind industry! Damn damn damn them all!