James Lovelock on wind energy as “vandalism” (UK)

Jan 27, 2013

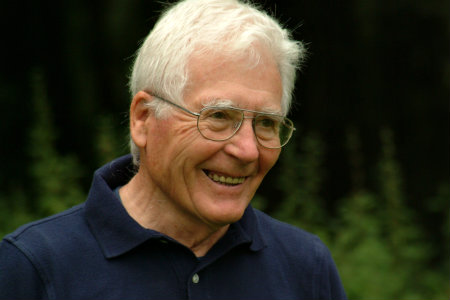

Editor’s note: The following was sent by James Lovelock, creator of the Gaia Principle and a founder of the international Green movement, to the Torridge District Council as testimony against the proposed Witherdon Wood Wind Turbine project. He by-lined it “Carey and Wolfe Valley Opposition to wind turbines.” His statement was circulated by his wife, Sandra Lovelock.

Click here for the original.

December 11, 2012

I am James Lovelock, scientist and author, known as the originator of Gaia theory, a view of the Earth that sees it as a self-regulating entity that keeps the surface environment always fit for life.

When I was a schoolboy in the 1930s, I cycled from my home in Kent to Land’s End and back. England then enjoyed a countryside that was seemly and probably the most beautiful anywhere; every mile of my joumey was along quiet lanes in fresh air unperturbed by traffic. I passed through an ever changing landscape that reflected in its vegetation a diverse geology going from the recent rocks of Kent back almost to the Precambrian in Cornwall. Our land had evolved by chance to become a place where humans lived in peaceful coexistence with the natural world and so became a part of it.

In that humane ecology, animals and plants benefited from our presence as we did from theirs. Blake’s dark satanic mills existed, but within densely populated cities that occupied only a small part of the whole and, from those cities, untouched countryside was no more than a tram journey away.

Sadly, that splendid countryside has all but vanished; replacing it is an agribusiness, factory farming that is more efficient at producing food but dull to look at and ecologically poor. At the same time, better cars and roads have enabled a vast expansion of suburbia and of second homes. England is becoming one large town haphazardly interspersed with ‘Greenfield sites’. The few sizeable stretches of original countryside that remain are in rural North and West Devon and Northumberland, and here people and wild life still coexist in a more or less seemly and sustainable fashion; these are places where woodland and hedgerows still serve both humans and wild life.

This remaining English countryside is much more than an aesthetic asset; Earth scientists now recognise our planet to be a self-regulating system that sustains habitability for its inhabitants and for this function we need the natural forests and life in the coastal and deep ocean waters to interact with the air and ocean and so keep a constant and habitable environment.

Ideally, humans should live in coexistence with the other forms of life so that our presence is benign; but in most of the world this rarely happens. We need to treasure the few exceptions, such as the North Devon countryside, so that they can be an example of how humans can live sustainably with the Earth. A whole library of books, going from Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selbourne to the New Naturalist series of the 1960s, testifies to the richness, health and beauty of England as it once was. We are fortunate indeed that some of it remains in North West Devon and we must look upon it as our most precious of assets.

It is true that we need a better way of producing energy, and there is little doubt among scientists—and I speak as one of them—that the burning of fossil fuels is by far the most dangerous source of energy. By using it to power industry, our homes and transport, we are changing the composition of the air in a way that will have profoundly adverse effects on the Earth’s ecology and on ourselves.

Anything we do in the United Kingdom about energy sources is mainly to set a good example before the other nations; if we drew all of our energy from renewable sources, it would make only a small change in the total emission of greenhouse gas. But such examples are needed and are something to be proud of. The benign way we, in North Devon, live with our countryside is also an example to set before the world about how to live sustainably with the Earth.

How foolish to set two such noble ideas in conflict and arrange that one good intention destroyed the other. To erect a large wind turbine on the Broadbury Ridge above the Carey and Wolfe Valleys is industrial vandalism that will diminish the regard with which the countryside is held and make the region vulnerable to urban development and unsustainable farming. Even if there were no alternative source of energy to wind, we would still ask that this 84 metre high industrial power plant was placed in less ecologically sensitive areas. Better still, we should look to the French who have wisely chosen nuclear energy as their principal source. A single nuclear power station provides as much as 3200 large wind turbines.

I am an environmentalist and founder member of the Green, but I bow my head in shame at the thought that our original good intentions should have been so misunderstood and misapplied. We never intended a fundamentalist Green movement that rejected all energy sources other than renewable, nor did we expect the Greens to cast aside our priceless ecological heritage because of their failure to understand that the needs of the Earth are not separable from human needs.

We need take care that the spinning windmills do not become like the statues on Easter Island, monuments of a failed civilisation.

James Lovelock

Comment by mtumba on 01/29/2013 at 1:03 pm

This is a beautiful statement, with perhaps one glaring exception. The spinning wind turbines ARE monuments to a failed civilization. A humane, environmentally holistic civilization cannot coexist with these industrial monstrosities. They are a sham energy technology, an environmental pollutant, a human and animal toxin and they only sustain greed, not life.